The Closed-World Assumption

Deus ex machina and Chekhov's gun are two expressions of a reader's most fundamental belief: if you are going to tell me a story, I'm trusting that you will give me everything I need to understand it. There's a term for this, most familiar to people programming classical AI: the "closed-world assumption".

The closed-world assumption [...] is the presumption that a statement that is true is also known to be true. Therefore, conversely, what is not currently known to be true, is false.

Put more directly: you're not hiding anything up your sleeves, right?

I want to walk through some of the ramifications of this assumption, because you can just as easily use it to improve your story as you can use it to shoot yourself in the foot. So: how do deus ex machina and Chekhov's gun relate?

Deus ex machina

Deus ex machina violates the closed-world assumption by introducing a plot-significant element from out of nowhere. Need to wrap up your alien invasion story quickly, but made the aliens too imposing to defeat with the plot elements at hand? Solve it like they do in pro wrestling: distract the referee and slide your hero a steel chair you hid under the ring. Whack! Down go the aliens from... the common cold? If the audience is in on your side, they'll turn a blind eye like that wrestling ref, and award you the pin. But it's far more likely they will sense your reasons for the deception, and sneer. Either:

- You didn't have the skill or foresight to set it up properly.

- You knew that your drama would collapse if you so much as mentioned the key element, so you had no choice but to keep it separate until the last instance... like putting a martian in a bubble, because you knew it'd drop dead as soon as somebody sneezed.

* Anthony Hopkins had 16 minutes of screentime to work with in The Silence of the Lambs. A backup NBA point guard will get more time than that in a single game, with the expectation that they'll log a couple assists, not create an iconic film character.

Neither reflects well on you as a storyteller. A plot shouldn't be allergic to itself, which is to say: spoilers shouldn't be that big a deal. People will complain about how much of the plot is given away in a modern movie trailer, but I think the marketers are right to do it. We watch magicians to be surprised. We watch stories to be moved. A writer's first responsibility is taking what's onstage at that moment — this scene, these characters — and making the audience give a shit. That's hard to do, because we get so little time to develop our story's elements.* The closed-world assumption is how the readers meet us halfway.

"I know you had to leave a lot of material on the cutting room floor, so I'm going to assume that all of the stuff that is here is meaningful, and treat it accordingly."

Chekhov's Gun

Chekhov's gun is what happens when the writer doesn't reward that assumption. Technically speaking, no crime has been committed against storytelling when a gun is introduced in Act 1 and goes unfired. It just speaks to how deep-seated that closed-world assumption is. It reaches beyond etiquette and becomes an unspoken contract between writer and reader.

Which may give the impression that there's something sacred here that we must solemnly observe. Not at all. The reader wants the writer to have some tricks up their sleeve. Murder mysteries deploy active countermeasures to confuse the reader, in the form of red herrings, and those are all part of the fun. Yet the closed-world assumption still holds, because these are distractions from the true culprit, who presumably also received a proper amount of investigation. If the murderer turns out to be somebody the story completely ignored, or worse, a slip-and-fall, you're going to disappoint the audience.

Plot Twists

Really successful plot twists respect the closed-world assumption, too. I remember my family pay-per-viewing The Sixth Sense in a hotel during a summer roadtrip. It's the only thing I recall from that vacation, in fact. Whatever monument we saw could not compete with the sensation, when that twist is revealed, of all those mental dominoes starting to fall. The closed world is suddenly enlarged as we realize it held a second meaning within it all along, hidden in plain sight. That's a huge jolt of excitement that is really hard for a writer to generate any other way.

His spin on The War of the Worlds made the aliens vulnerable to water, which is somehow clunkier than the cold.

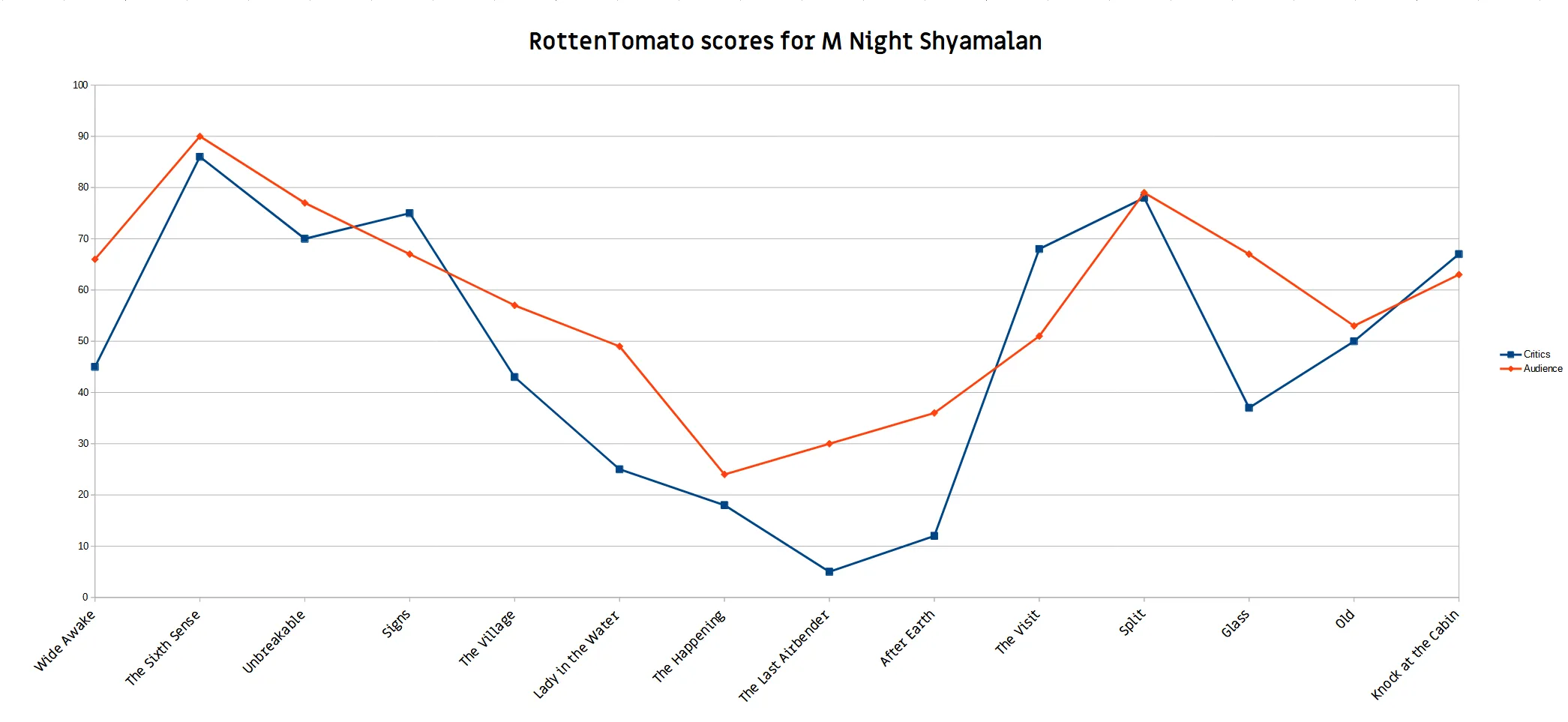

Shyamalan, understanding the power of this jolt, has continued playing around with the closed-world assumption throughout his career. A lot of the time, he's the one who has gotten zapped.

The Village, the start of his slump, is as literal a violation of the closed-world assumption as you can get.

*10 Cloverfield Lane and Silo exploit this same pressure to hook an audience. And in Silo's case, I quit on the show one episode before the season finale, and just looked up the story in Wikipedia. It's a volatile hook.

His latest movie, Knock at the Cabin, puts a biblical choice on the protagonists' shoulders. Will you sacrifice your child to save the world? The issue is that this choice is being forced on the protagonists by a gang of home-invaders who have seen visions of doomsday... not the most credible bunch. The truth of the matter lies outside the closed world of the cabin. That puts major pressure on the reader.* Readers are used to dramatic irony, in which we get to watch benighted characters make tragic mistakes due to their lack of knowledge. Don't keep us in the dark!

But Shyamalan wasn't willing to let the audience squirm for too long. In fact, his participation was contingent on script changes. The book (and its initial adaptation by Steve Desmond and Michael Sherman, which was apparently a hot commodity in Hollywood) had a more grim, ambiguous ending. Shyamalan said:

I include this quote mostly because it is a great insight into Shyamalan's success in Hollywood. The man's been working steadily for decades now, having survived the kind of reviews that would get any other director exiled to TV, and it's because he has a very definite idea of who his audience is, and how he wants them to be treated.

The movie came to me as a producing entity where the writers and the directors who were on wanted to make a straight adaptation of the book, just moment for moment, straight adaptation. And that's how it came to me. And then I said, "I love this premise so deeply. And I think you guys are onto something, I really do. I don't believe in this story when it went left. I can't get behind that. And I think my audience, I wouldn't want to have them experience that.

"It Was All a Dream"

Once you buy into the closed-world assumption, "it was all a dream" seems like the most obvious unforced error, but the timing matters. The Wizard of Oz pulls this off with zero consequence, for instance, and it can do so because Dorothy wakes up from her dream right at the end. Part of a story's job is gracefully shutting down this pocket universe it has created. "And they all lived happily ever after" is the classic, reassuring the sleepy child that they won't miss anything exciting if they drift off into a dream of their own. Which is why "it was all a dream" strikes me as perfectly valid nudge to the adult: psst. hey man, wake up. It's over. Time to go back to reality. But your mileage may vary.

Remember Me, a Robert Pattinson romance, has been doing the rounds on Twitter lately for being a stealth 9/11 movie. The big twist is revealed when, near the end, we see a classroom blackboard bearing the fateful date.

I haven't seen it, but I think that's an interesting choice on the grounds of verisimilitude alone. National tragedies shatter the bubble of the everyday in exactly the same fashion, but of course invoking something so dire in a run-of-the-mill drama is setting your story up to fail. One of the most natural human reactions to the sudden appearance of something incredibly serious is laughter, after all.

Sidenote: I think the reason that Remember Me is coming up now, after so many years, is that Twitter is heavily populated by Gen Z, and their lack of firsthand experience with 9/11 gives them much more ironic distance towards it. Older generations would shrug the movie off as being in poor taste, or ham-fisted in the execution, but they have a bit of guilt for not seeing it as such a big deal, and this provides an outlet for that guilt.

1 To be fair, a Mission: Impossible script may have a quota for this moment, due to the perfectly lifelike masks that the heroes have access to. In the best case scenario, you get the fun Wolf Blitzer cameo in Fallout, where they stage a news broadcast to trick a bad guy into a gloating confession. And typically, these are minor gags that inject a bit of excitement, and can usually be seen coming a mile away. (Somebody acting out of character? Mask.)

2 He's good with traditional screenwriting, too: he won the Oscar for The Usual Suspects, which is another great plot twist that's fully compatible with the closed-world assumption

In the middle of a story, however, "it was all a dream" can be a show-stopper. Mission: Impossible movies pull this move constantly, and it drives me nuts.1 Christopher McQuarrie is Tom Cruise's creative partner in these things, and he is a savant when it comes to blockbuster storytelling.2 I can't name another screenwriter with more practical, hands-on experience in managing the flow of emotion and information to keep a mass audience engaged. Top Gun 2 is a coup in that regard: there's nothing textbook about rehearsing the third act setpiece half a dozen times in fairly sedate briefing room scenes, but it was exactly what we needed in order to be in the moment when it all went down.

In Mission Impossible: Fallout, that exact same maneuver is extremely obnoxious. I know why they did it: we have a "people in a room, talking" scene that is running for four minutes. There's a map and some visual aids, but four minutes is a lifetime in a film franchise built around hissing bomb fuses. So when Ethan Hunt asks precisely how he will recover the MacGuffin, we cut to live action: whew, finally. And even better, we get to see a mission going awry, which leads to our hero gunning down some cops in cold blood. It's a chilling Rubicon moment for both the character and for Tom Cruise, who is hellbent on protecting Ethan's heroic persona. But then we discover that those beautiful strings in the soundtrack were a clue that this whole sequence was a hypothetical.

There's the difference. In Top Gun 2, the rehearsal was accurate, and when things go sideways, it counts. In Fallout, they wanted to juice a scene and couldn't do it without leaving the reality of the story. So they tried to have their cake and eat it too. They got the thrill of showing the hero doing something villainous without needing to honor any of its consequences. Which makes me wonder: how we can wield the closed-world assumption more responsibly?

Stakes

Every writer will, at some point early in their journey, write a story with preposterously high stakes. If the heroes don't do X, then the world's gonna blow up, everybody dies, etc. And every writer, having done this, will reread what they wrote and be puzzled at how unexciting it feels.

Once again, we're seeing the closed-world assumption in action. Things like the end of the world, which is objectively exciting in reality, mean nothing in fiction because the world is too big to fit inside your story. All you have to work with are the pieces you've laid out. So if you want the reader to feel that the stakes are apocalyptic, you need to threaten the closed-world itself.

That can take different forms. Take The Mandalorian. With the eponymous hero being a guy who took a vow to hide his face, Baby Yoda (aka Grogu) is the natural receptacle for all of the audience's good felings — and that's leaving aside our instincts to find babies adorable. So obviously that writing team can provoke a massive threat response by putting Grogu in peril. Brian de Palma sent a baby sailing down the steps of Union Station in The Untouchables on the strength of that same principle.

That's the most obvious example, in which you threaten some element of your closed world that the readers care about. The less obvious (and more exciting) version is when the writer threatens the closed world itself, by making the story harder to tell.

I watched Brian Duffield's horror movie No One Will Save You this weekend. I was completely engrossed. The Baby Yoda effect was in play: the star, Kaitlyn Dever, is a phenom, and I became a fan of hers through Justified, in which she played a baby-faced teenager trying to survive in a violent criminal underworld. Seeing her in duress once again inspired an extra measure of protectiveness in me that was purely metatextual.

I tweeted this during The Last of Us.

Textually speaking, it was Duffield's willingness to punch the gas that got me so invested. No One Will Save You is a home-invasion movie about aliens, and that alien wastes no time invading that home. My assumption as a viewer is that we were going to spend forty-five minutes, minimum, building up to it. In Signs, the iconic "Move, children! Vámanos!" moment comes at the 58 minute mark, and that was so shocking because we fully expected Shyamalan to keep hiding the alien, even an hour into the story.

Duffield's alien is on the loose in 15 minutes, which leaves him with 72 minutes he needs to fill with... what? I had no idea. This is a thrilling position to put your reader in, and a risky position to put yourself in as a writer. Because you're making a strong claim: I'm going to find a way to top this. I know you can only see a corner of our closed-world right now, but stick with me, I'm going to fill it out with stuff that's even more interesting.

George RR Martin would have finished ASOIAF years ago if he didn't adopt this strategy, but unfortunately he did. It was a Faustian bargain — nobody would have gotten so invested in the story without all of those shocking deaths, but with each one, Martin closed off another narrative escape route.

If that high-wire act works, you are applauded. If it doesn't, your story goes splat. That's compelling in a way that has nothing to do with the story's content: it's a rare opportunity for the writer themself to be a daredevil. No One Will Save You kept working for me, but Duffield carries the same attacking mentality all the way to the last beat of the film, which some people bumped against. I'm open to surprising endings, because we've reached the end of the road. If a writer makes a bad decision in the last scene of the movie, I have to live with it for another two minutes, max, so I'm easy to please.

Takeaways

Similarly, many TV shows have woefully misjudged how interesting certain characters are to the audience. Matthew Weiner, perhaps understandably, couldn't resist putting his son into scenes.

The hardest thing about writing with the closed-world assumption in mind isn't, as you might expect, that the writer can never know exactly what will draw the reader's attention. Sure, it's a safe bet that readers will be horrified if an innocent animal is put in harm's way. Save the Cat! is the title of a hugely popular book on screenwriting, after all. But go see Alien in a repertory theater if you ever get the chance. When Ripley turns back to save Jonesy the cat, you will have an entire auditorium full of people, cat-owners included, pressing their hands to their face, practically shouting, "Are you nuts?! LET THAT CAT DIE." Now either screenwriter Dan O'Bannon was luxuriating in the wholesome sadism that horror movies encourage, by taunting us with Ripley's imminent escape before re-endangering her... or maybe he was anticipating that people would be annoyed if an innocent cat was left to its death, and he was just covering his bases. The latter seems more plausible to me. Could he have imagined, sitting in his office, staring at a typewriter, just how scary that xenomorph would be? Or the fact that the filmmaking would be firing on every cylinder?

This kind of anticipation is not the real pitfall, because I think that beta readers can flag these moments for you. (And if you don't have beta readers, yourself-in-six-months will probably have enough perspective.)

No, the tricky thing is that writers operate from within the open-world assumption. For us, it's always possible to introduce a new element to the story. In fact, that's job number one: to keep finding interesting stuff to pump into the storyworld. We always need more juice, more setpieces, better characters, cooler backstories. That creative process is so demanding that it can be hard to know when to stop, settle in, and be confident that you've got all the pieces you need to execute the story.

One thing I'm going to keep in mind, having seen No One Will Save You, is that you can really take advantage of the information asymmetry between you and your reader. I came into that story almost completely cold: I knew it was an alien home invasion. I got precisely that within the first fifteen minutes. After that tidy speedrun, I was completely bought in and open to anything Duffield wanted to try next -- he had earned that trust.

So if you're writing a story, it's worth asking: can I create a closed-world within this closed-world? I'm not talking about a frame story, or a Narnia-like otherworld for the characters to visit. I'm talking about a kind of narrative vestibule, which is self-contained and self-sufficient, to the point that it could plausibly sustain the full story. Because if you can, then you can knock that wall down and welcome your reader into the wider world, at which point you are in business. I suspect that, having finished a story and knowing the shape of the plot, you can go back and strategically screen off certain parts of it, setting the reader up for that surprise.