Lock and Key

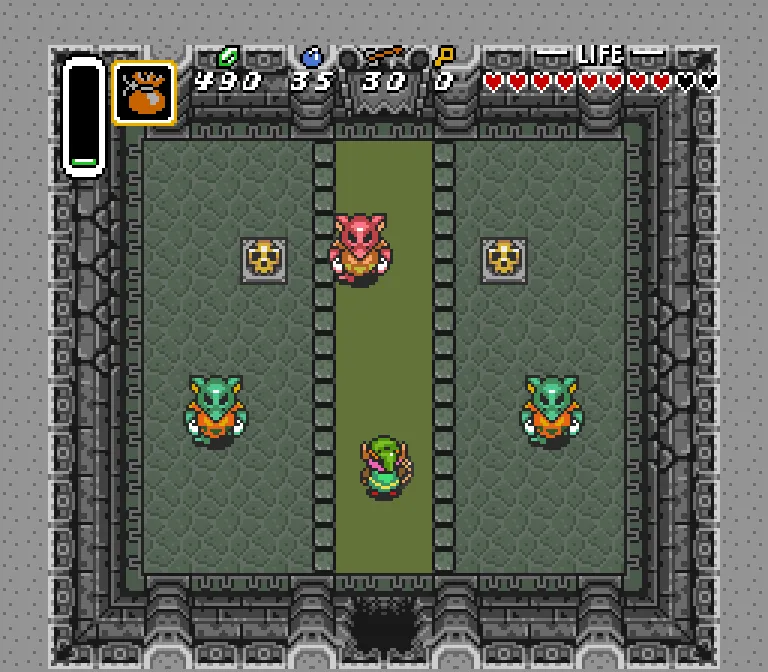

I resume The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past somewhere in the middle of the game's fifth dungeon, the Palace of Darkness. It's been so long that, were I playing on an SNES, a harmonica solo would have been required to clear the dust from the cartridge, but since I am playing on

The rats are mimics. If you move left, they move left. If you move forward, they move forward, etc. The green variety are harmless. While they play Simon Says, Link can walk right up and slash them to death. But the red variety spits fire, and this fireball outpaces any projectile Link has. Which means I have to devise some oblique angle of attack. I try my boomerang — nothing. I plant a bomb, then maneuver the rat onto it — nothing. I charge my sword, sneak around behind the guy, and unleash a whirlwhind — it is ineffective. (The greens did die to sword attacks, remember.) I fling a pot and it shatters over its head like I’m fighting the terminator.

Trying to crawl out of the solution space’s local maxima through this kind of trial and error is not exactly fun. But it is deeply compelling.

Because LTTP recognizes the psychological value of a locked door. They fascinate us. Even if we don’t know what’s behind them — it could be a broom closet — the simple fact that they’re locked suggests there is some valuable secret just behind them. A locked door is its own motivation. At times, LTTP is less a game than a Skinner box built to study this impulse. Like rats, we are run through mazes (battling other rats as we go!) relying on our automatic urge to discover what’s behind that door. When we open one, we get our cheese.

I can’t hear that jingle without a hit of endorphins. Only a few games can induce this kind of compulsion. Civilization gooses your brain stem with a similar question: “I wonder what’s under this fog?” But as appealing as it is to solve puzzles and open locked doors, it’s equally repellant to be unable to open them.

There are no degrees of success with a locked door. You either have the solution or you don’t. That means there’s no gradient between success and failure, only frustration preceding epiphany. That’s why I’ve abandoned so many Zeldas mid-stream: that ratio of frustration to satisfaction became slightly skewed.

The frustration of locked doors isn’t just a problem for the dungeons. It applies to the overworld as well. Though it’s an expansive, ostensibly open space, the overworld is a macrocosm of the dungeons: lots of locked doors. These take the form of cordons made of boulders or fences. It’s an elegant way to direct play while maintaining an illusion of openness, but it can seem contrived. The idea that Link — who apparently has the agility of a vacuum cleaner — is stymied by wooden pegs until he acquires a giant mallet is a little silly. A locked door’s meant to be an obstruction, but there are fun obstructions and spiteful obstructions. With these inexorable mirror mice, I feel like my key to my own front door isn’t working. Come on, Miyamoto: I just detonated a cherry bomb the size of a bowling ball under that thing’s feet! How is it alive?!

Wait, have I tried my arrows yet? That does it: the appropriate strategy is to line up just barely offset with the red terminator mouse. Fire your arrow, and while the projectile is midflight, dash to the left. The terminator will move to his left as well, directly into the arrow’s path. The door rumbles open — a new room awaits. Forget everything I said about frustration.